[Note: all of the frame grabs below (save one) have been taken from the 2002 DVD edition of PURPLE NOON and not the new Criterion Bluray that debuted on December 4th. The previous DVD version was essentially a rip of the 1996 VHS version which corresponded with the Martin Scorsese-led revival of NOON. The new restoration, as you can see from DVD Beaver's coverage, is a major improvement. At the bottom of the post, I've included an image comparison.]

Rene Clement's PURPLE NOON is a 1960 adaptation of Patricia Highsmith's dark psychological crime novel, The Talented Mister Ripley. Most people are probably familiar with the 1999 version directed by Anthony Minghella and starring Matt Damon, Gwyneth Paltrow, and a pre-overexposure Jude Law.

Minghella's film (at least, my memory of it; it's been a while) polished the story into a very pretty piece of Oscar chum, luxuriating in the Mediterannean setting and lingering on Jude Law's sun-blanched abs.

Highsmith's book (which, for the record, I have not read) centers on Tom Ripley, a young man living hand-to-mouth in New York City, who gets his big break when he's sent to Italy to retrieve Dickie Greenleaf. Greanleaf's father is tired of his son's irresponsible playboy lifestyle and wants him back in the US, tending to the family's business. If Ripley succeeds in retrieving the young Greenleaf, he'll be paid $5000. Trouble is, Ripley is a budding sociopath. He gains the elder Greenleaf's trust by pretending to be good friends with Dickie (when, in fact, the two men barely knew each other). Ripley's a social climber who's not afraid to dig his sharpened crampons into the back of whoever interferes. This, naturally, includes Dickie Greenleaf. Ripley never ends up bringing Dickie back to the States. He settles for killing him and methodically assuming his identity.

A key line from Minghella's film was Matt Damon's Ripley sniveling "I always thought it'd be better to be a fake somebody than a real nobody." This is Minghella's on-the-nose summation of Tom Ripley's internal drive. Thankfully, Clement's film is free of any such psychologizing. PURPLE NOON is equal parts a cool, quiet character study and a sort-of criminal procedural. PURPLE NOON's Ripley doesn't necessarily begin as an aspiring criminal but he's not above busting into the field when he sees an opening.

Minghella's film (at least, my memory of it; it's been a while) polished the story into a very pretty piece of Oscar chum, luxuriating in the Mediterannean setting and lingering on Jude Law's sun-blanched abs.

Highsmith's book (which, for the record, I have not read) centers on Tom Ripley, a young man living hand-to-mouth in New York City, who gets his big break when he's sent to Italy to retrieve Dickie Greenleaf. Greanleaf's father is tired of his son's irresponsible playboy lifestyle and wants him back in the US, tending to the family's business. If Ripley succeeds in retrieving the young Greenleaf, he'll be paid $5000. Trouble is, Ripley is a budding sociopath. He gains the elder Greenleaf's trust by pretending to be good friends with Dickie (when, in fact, the two men barely knew each other). Ripley's a social climber who's not afraid to dig his sharpened crampons into the back of whoever interferes. This, naturally, includes Dickie Greenleaf. Ripley never ends up bringing Dickie back to the States. He settles for killing him and methodically assuming his identity.

A key line from Minghella's film was Matt Damon's Ripley sniveling "I always thought it'd be better to be a fake somebody than a real nobody." This is Minghella's on-the-nose summation of Tom Ripley's internal drive. Thankfully, Clement's film is free of any such psychologizing. PURPLE NOON is equal parts a cool, quiet character study and a sort-of criminal procedural. PURPLE NOON's Ripley doesn't necessarily begin as an aspiring criminal but he's not above busting into the field when he sees an opening.

***

Okay then: it's been a long week. This was supposed to be posted Tuesday the 4th but I got ensnared in the mucousy tentacles of the flu and -- over a week later -- I've lost a bit of my momentum. So what follows will be a bit of a slide show, illustrating a few of my favorite moments from NOON, which I truly believe is one of the best psychological thrillers, ranking with Hitchcock's work. To call it (or really any other solid thriller) "Hitchcockian" is a bit of a back-handed compliment since it implies that what it does well, it does only in service of someone else's more well-known work. Plus, Clement's focus is different than Hitchcock's. He's not as concerned with the suspense (though he pulls it off effortlessly). He's more into the arcane details that make up Ripley and Greenleaf's world. So here are my rather randomized thoughts about said details...

The first thing I noticed about Criterion's NOON is how vastly different they've packaged it compared to Miramax's 1996 rerelease. I'm going to venture a theory that -- pre-internet -- the best (and perhaps only) way to get your foreign/art house film seen by more than just the usual foreign/art house constituents was to market it as some sort of softcore erotic romp (indeed, that's how Miramax rose to prominence in the '80s).

The box cover on the left depicts a scene that barely happens in NOON. It promises a lot of steamy, PG-13 man-on-woman action. It lies. Sure, Greenleaf (Maurice Ronet) and his long-suffering lady love Marge (Marie Laforet) have a few brief moments.

But the real lust affair in NOON is, ultimately, between Ripley and Ripley.

So the Criterion cover artwork is a lot more accurate with its simple, stunning image of Alain Delon's Ripley and a barely superimposed, warped Greenleaf.

While the film is certainly not the erotic skinfest Miramax marketed, it is very sensual. Ripley is\ attracted to the hedonistic trappings of Greenleaf's playboy lifestyle: the clothes, the boats, the ornate hotel rooms, the carousing, the food and drink... One of the most important signifiers of Greenleaf's One Percenter life is the food he enjoys and how he enjoys is. My favorite little moments in the film almost all involve food and/or religious overtones (which led me to the title of this post; Google it).

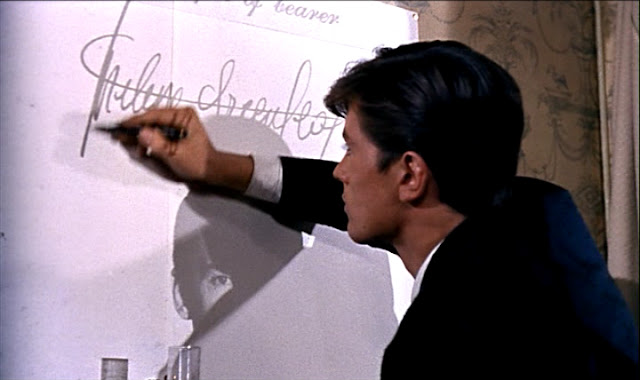

The film opens with a close up of a cafe table where Greenleaf and Ripley are enjoying drinks and plotting their next move. Ripley is also showing off his well-honed talent for forgery.

The two men proceed on what we assume is a typical evening for them: buying a blind man's cane (just because they can), romancing a bejeweled socialite, and getting blinkered. For Greenleaf (and, by proxy, Ripley) the thesis offered in Věra Chytilová's DAISIES -- "if everything's spoiled, we'll be spoiled too" -- is the whole of the law.

For the film's next forty minutes or so, Ripley's sycophantry inspires equal parts amusement, flattery and alarm in Greenleaf. Greenleaf is quick to point out to Marge that Ripley has “brains but not enough money” and, worse, “wasn’t well-bred," a fact borne out by Ripley's inability to properly hold his knife and fork at dinner. Greenleaf gives a quick, condescending crash course on utensil etiquette.

Eventually, of course, Greenleaf's bemusement with Ripley becomes contempt and Ripley's obsession with Greenleaf becomes deadly. While both men are on Greenleaf's boat, Ripley stabs Greenleaf, wraps him in a tarp, and chucks him overboard. Two interesting items follow the murder; first, Ripley tears ravenously into a baguette, like he's engaging in some sort of savage, twisted communion rite. Next, the seas become vicious. The wind and waves churn, chucking the ship around and knocking Ripley overboard. It's a (very intentional) deus ex machina moment (shades of Jonah's rebellion).

The film is beautiful by the way; Clement and cinematographer Henri Decaë (THE 400 BLOWS) masterfully exploit the Mediterranean's vibrant cerulean seascape and the burnt umbers and oranges of the surrounding architecture. Clement's sensual approach to Greenleaf's (and, eventually, Ripley's) world is rife with street-level details. One of my favorite moments in the film is when Ripley, following the murder of Greenleaf, steps out on the town in his victim's clothes.

It's one of the only times we see him enjoy the spoils of his homicidal work. He rambles through the fish market, taking in the exotic sights and playing at being the type of worldly, well-heeled fellow who, well, visits fish markets and knows what he's looking for.

Earlier, Greenleaf complained to Marge that "all (Ripley) thinks about is money." Here, Ripley takes a breath and stops worrying for a minute. Granted, his innocent smile belies the fact that he's a murderous fraud. And that's the interesting thing about NOON (and Highsmith's Ripley): we kind of root for the bad guy. For starters, it helps that Greenleaf is a condescending, self-loving boor. In addition to his passive-aggressive abuse of Ripley (whom he seems to keep around just to have a sycophant), Greenleaf is brutish with Marge. Prior to his untimely demise, Greenleaf takes delight in tossing Marge's current labor of love -- a prized manuscript she's working on about Fra Angelico -- into the ocean.

An even more twisted reason I found myself in Ripley's corner, however, is his undeniable skill. He's clearly got a knack for identity theft; it's not for nothing he's the "talented" Mr. Ripley.

His attention to detail is impeccable; nothing escapes him. And he works hard at being a fraud. There's a particularly great scene near the end where he has to prepare a room to look like it's been lived in by Greenleaf for days. The gentle care he takes to muss up the bed, put spent cigarette ends in the ashtray, and crumple the paper just so... it's hard not to admire the creep.

After Greenleaf is killed, the remaining hour of the film becomes a quiet journey into Ripley's mind as he adapts to his new identity and evades detection by Marge and others in Greenleaf's circle. Unfortunately, one of Greenleaf's buddies, Freddy Miles (Bill Kerns), suspects Ripley is up to no good. It ends badly for Freddy.

Again with the food. Freddy dies in a fumbling shower of groceries, after being struck on the head with a jade statue of the Buddha. After his second murder, Ripley does what any of us would do and has a meal of an entire roast chicken.

To dispose of Freddy's body, Ripley has to pull the whole "my friend drank too much"/WEEKEND AT BERNIE'S stunt. It leads to one of my favorite shots in the film:

Two red-clad priests materialize out of the black on the dimly lit street. The priest on the left has a pious contempt for Ripley and his "inebriated" friend; the guy on the right can't even bring himself to look. It's a great little moment.

Another similar moment: at the morgue, Ripley and a few others are called in to view Freddy's body:

The black-gloved woman -- a moneyed society type played by Elvire Popesco -- bluntly laments that “we’ll all end up like this”. Meanwhile, the nun behind her stares daggers into the negative space...

... where Ripley emerges. The nun's cold eyes fix him. She knows what's in a man...

... but says nothing. It's all we see of her but it's another instance of Clement subtly juicing the suspense without playing any false notes.

One more favorite moment and I'm done. Ripley pushes his way into Marge's life, not quite seducing her but definitely playing up the "friends mourn together" card.

In a scene where she begins to come to terms with Greenleaf's absence, Ripley moves in to console her. While they're having this intense exchange, the scullery maid enters, proffering what I'm sure is an expertly crafted salad:

In a little gesture of melodramatic despair, coupled with unappreciative entitlement, Marge declines:

It's another example of how Clement -- and Ripley -- perceive the hedonistic ruling class.

Highsmith was upset by what she thought was a bowdlerized finale but I think Clement leaves it just open enough to where Ripley’s fate could go either way. It's fitting that the film ends on yet another shot of Ripley enjoying the trappings of the life he's stolen:

One more favorite moment and I'm done. Ripley pushes his way into Marge's life, not quite seducing her but definitely playing up the "friends mourn together" card.

In a scene where she begins to come to terms with Greenleaf's absence, Ripley moves in to console her. While they're having this intense exchange, the scullery maid enters, proffering what I'm sure is an expertly crafted salad:

In a little gesture of melodramatic despair, coupled with unappreciative entitlement, Marge declines:

It's another example of how Clement -- and Ripley -- perceive the hedonistic ruling class.

Highsmith was upset by what she thought was a bowdlerized finale but I think Clement leaves it just open enough to where Ripley’s fate could go either way. It's fitting that the film ends on yet another shot of Ripley enjoying the trappings of the life he's stolen:

Nice post thank you Phukwane

ReplyDelete